Evolution is a fascinating and perplexing phenomenon. The idea that all mammals, including humans, are somehow connected is interesting. One that can be difficult to grasp: where do we locate evidence of evolution? There is significant evidence of our evolutionary past, which may be traced back to early primates, Neanderthals, and finally to the present Homo sapiens we have become.

A spectacular spot to see evidence of evolution? Our own bodies!

Many of our internal and external qualities are simply inherited from our forefathers. Many of these characteristics no longer serve a useful role in our daily lives. Even while many people no longer forage for food or wander as nomads, we nevertheless retain these nearly useless traits. They were passed down to us from a time when they were necessary for survival.

Take, for example, the unusual sensation of goosebumps. It is not a random event. When our mammalian ancestors encountered freezing temperatures, they had a well-known strategy for dealing with the situation. Goosebumps acted as a method for increasing surface area and retaining heat. When we are chilly, a muscle associated to our arm hairs contracts, forcing the hairs to stand upright and leaving bumps on the skin.

This physiological response serves no useful purpose in our current lifestyles. Aside from telling us that we should have packed a coat, modern mammals continue to exhibit this inherent tendency. For example, when faced with cold weather. You may have seen a pigeon puff up on a cold winter day, stretching out its feathers to be warm. If that’s not evidence of evolution, what is?

Furthermore, when an animal feels threatened, such as when you startle a cat, their fur puffs out. This defense mechanism is an old adaptation designed to deceive potential attackers by creating the illusion of increased size.

However, there is one characteristic that unequivocally demonstrates signs of evolution.

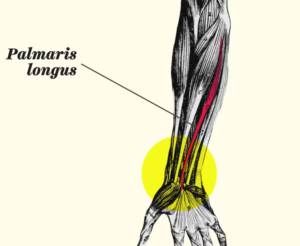

One particularly astounding piece of evolutionary evidence is found in our arms, notably our tendons. A tendon has been evolutionarily phased out in over 10-15% of the human population, indicating that we are still far from the end of evolution.

This tendon is linked to an ancient muscle called the palmaris longus, which was primarily employed by arboreal primates like lemurs and monkeys to move from branch to branch. As humans and ground-dwelling apes, such as gorillas, no longer rely on this muscle or tendon, both species have gradually lost internal function.

Nonetheless, evolution moves at its own pace – slowly – and approximately 90% of humans still have this vestige trait passed down from our primate progenitor. To determine whether you have this tendon, place your forearm on a table with your palm facing upward. Place your pinky finger next to your thumb and elevate your hand slightly off the surface. If you notice a raised band in the middle of your wrist, you have a tendon attached to the still-existing palmaris longus.